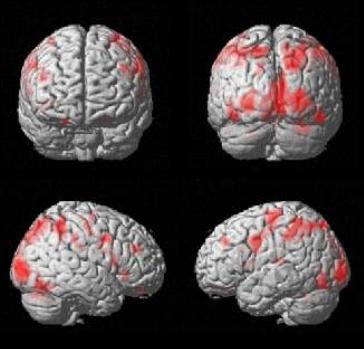

If you see psychology research in the press these days, chances are it comes complete with a pretty fMRI picture, the ones with the brain covered in lights showing which parts are working more. It’s less likely that you’ve seen anything referring to EEG, a method that also measures brain activity but is based on the electrical activity of neurons firing instead of where blood flows. Is that because EEG isn’t as good as fMRI? Are they redundant?Some neuroscientists argue EEG is actually superior. The problem with fMRI is that it mostly, if not solely, tells us about functional localization – which part of the brain is responsible for carrying out a particular mental process or operation. However, fMRI isn’t able to get to the level where neurons differ in terms of their functions and connections to other neurons. Besides, it’s hard enough to make these place-to-function mappings when one process activates many brain regions or when one brain region is active for many tasks.

Instead, brain research should focus on when things happen rather than where. Both within and across brain regions, important information is conveyed by the timing with which neurons fire; sometimes together, sometimes in sequence, or sometimes in rhythm. These time-sensitive activities will all fly under the radar of fMRI. Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. EEG, on the other hand, records activity every millisecond. Time data also contains multiple pieces of information about neuron firing (such as the rate, the strength, and the synchrony across regions), making it richer than simply knowing where in the brain activity is occurring. It isn’t perfect; these methods have their own drawbacks (for example, EEG is as bad with spatial information as fMRI is with time) and it doesn’t make sense to completely ignore the information provided by fMRI. But perhaps we will learn much more about the brain and how it functions by studying when it is active rather than where it is active.

EEG, on the other hand, records activity every millisecond. Time data also contains multiple pieces of information about neuron firing (such as the rate, the strength, and the synchrony across regions), making it richer than simply knowing where in the brain activity is occurring. It isn’t perfect; these methods have their own drawbacks (for example, EEG is as bad with spatial information as fMRI is with time) and it doesn’t make sense to completely ignore the information provided by fMRI. But perhaps we will learn much more about the brain and how it functions by studying when it is active rather than where it is active.

If EEG is arguably superior to fMRI, why do we see so much fMRI research in the press as well as psychology journals? Part of the reason is that people find fMRI images so convincing. Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Keehner and colleagues expanded on this work and concluded that it happens because people think the fMRI image is an actual picture of the brain at work. A ‘real’ picture of the brain is more impressive than a bar graph or even EEG data. This (incorrect) impression is likely a big part of why so much fMRI research appears in the press and why more and more funding is going to fMRI projects.

Keehner and colleagues expanded on this work and concluded that it happens because people think the fMRI image is an actual picture of the brain at work. A ‘real’ picture of the brain is more impressive than a bar graph or even EEG data. This (incorrect) impression is likely a big part of why so much fMRI research appears in the press and why more and more funding is going to fMRI projects.

What is a neuroscientist to do if EEG might tell us more about the brain but fMRI is also useful and much more convincing to the public? The best route might be to ride the wave of the future by combining methods and collecting spatial and temporal data at the same time. You should always bring a gun to a gunfight, but bringing a knife and a gun is even better.

But the best weapon, of course, is Christopher Walken.

Cohen MX (2011). It’s about Time. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 5 PMID: 21267395

Keehner, M., Mayberry, L., & Fischer, M. (2011). Different clues from different views: The role of image format in public perceptions of neuroimaging results Psychonomic Bulletin & Review DOI: 10.3758/s13423-010-0048-7